What can history teach us for the task of rapid transition in the face of climate change and corrosive inequality? Historian Molly Conisbee looks at how communities adapted during Britain’s dramatic urban growth and upheaval in the 18th and 19th centuries. She reveals how people shared idle assets, reducing the need for ‘stuff’ and spread financial risks, for example by setting up women-run ‘Weather Clubs’ used for mutual saving. The struggle for greater economic, political and social equality, she finds, must be at the core of any resilient or rapid transition.

Credit where credit’s due

by Molly Conisbee

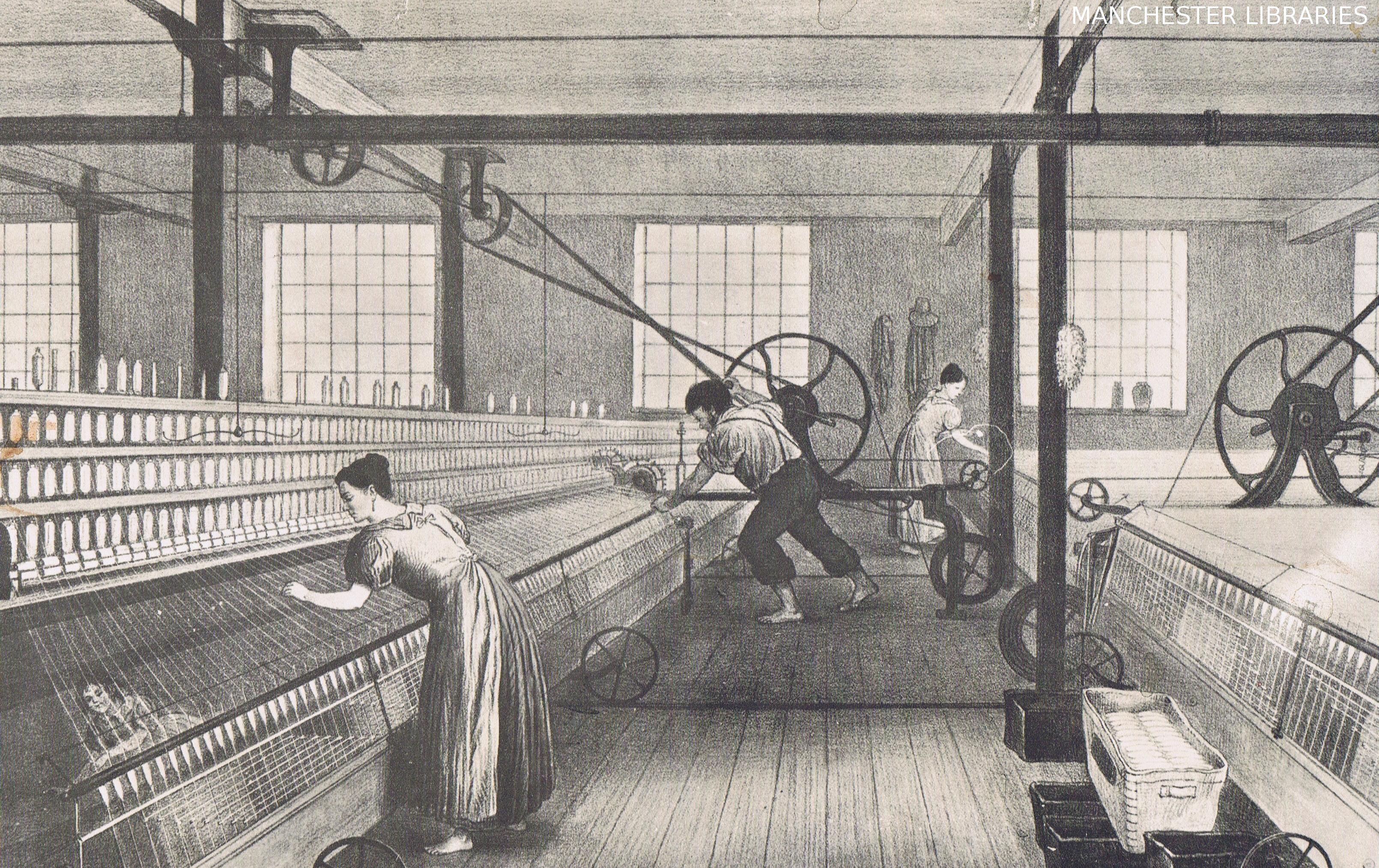

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, British cities struggled to cope with unprecedented population growth. During the first three decades of the 19th century the population expanded by 56% in England and Wales, and 50% in Scotland. In 1801, London was the only city in Britain with over 100,000 residents. By 1831, six more had passed that threshold, including Manchester, Bradford and Glasgow.

The 19th century population was a mobile one. By 1851 over half of urban workers was not living in their place of birth, as huge numbers of people moved from country to city, in search of work. Some towns had particularly high levels of migrants – Bradford had around a 70% migrant population. Some moved and settled but there were also some quasi-permanent migrant populations, who moved from place to place as employers required.

Most migrants moved as teenagers or young adults – two thirds of migrants to cities in the 1850s were aged between 15 and 29. As one contemporary from the Lune Valley observed, ‘almost all of our boys go off to the manufacturing districts when they are 12 years or younger.’

Living conditions were usually appalling. Speculative house building simply did not keep up with population growth, and many ended up living in cellars, lodging houses and multiple occupancy ‘rookeries’ in quite atrocious circumstances. A young Engels documented some of these conditions in The Condition of the Working Classes in England. Britain by the mid-19th century was the greatest manufacturing economy of the world…and the greatest slum, extensive and squalid.

19th century working-class life was thus tough, dirty, disease-ridden and often brutally short. But it wasn’t all gloom and doom. Mass life in the cities arguably enabled new ways of organizing and thinking politically. Conditions of density helped develop and shape ideas about mutualism, self-help and other ways of surviving, that may hold ideas for sustainable change today. The sheer volume of associational activities that new life in the city created is astonishing.

One strategy for survival involved new ways of keeping the local economy working through new forms of credit. If you look up the word ‘credit’ in the Oxford English Dictionary you will find more than 12 definitions. These include the ‘ability of a customer to obtain goods or services before payment’, but also ‘public acknowledgment or praise’, ‘a source of pride’ or ‘good reputation’.

A study of a community living in the Rothschild Buildings in the East End of London at the turn of the last century, shows that hundreds of families would have gone to the workhouse, but for those small tradesmen giving them credit for the bare necessities of life, tiding them over the pinching time. This can hardly be called philanthropy, since those that extended credit needed to keep their own businesses afloat. But it does indicate the complex eco-systems of local financial arrangements that working-class communities developed for themselves.

A lot of working-class financial support came through development of localized credit schemes. In 1902, a study conducted by Sidney Dark found that many such schemes were run by publicans and licensed grocers in working-class urban areas. These included goose clubs and Christmas clubs. Some clubs were semi-philanthropic in nature. School clothing and coal clubs often operated in a way that the family or individual made a contribution to goods and the rest was made up by the school or a local community group. This was another way of keeping limited funds circulating in the community.

Other clubs were more clearly rooted in self-help. One such example was a Weather Club, where a group would take a week from Friday to Friday and each day should it rain during the whole 24 hours pay a penny; for fog two-pence; for snow three-pence and a thunderstorm four-pence and then the amount was shared at the end of the year. As one member said ‘It does not come to a very large amount, but it makes a little extra at the time you really need it.’

Pub clubs were common among regulars. They were in part an excuse for social gatherings and would usually provide for a boozy summer outing and a Christmas share out of any surplus.

A survey by the Women’s Cooperative Guild in 1901-02 found that practically every person they spoke to in poorer districts of cities relied on some form of credit club, and bought everything from boots to drapery and furniture through them. The usual structure of such clubs involved the payment of 21 instalments of 1 shilling in exchange for £1 worth of goods.

Credit clubs were often privately run by women, which add an interesting gender dynamic to the history of informal credit, and often structured as so-called ‘drawing clubs’. That meant that lots would be drawn to decide the order of payment amongst the members, with any surplus paid to the treasurer. Sometimes a street draw would be organised to help a neighbour who had fallen on hard times, or needed money quickly for a funeral or other family crisis.

Credit clubs existed for anything and everything – toys, chocolate, even face powder! But they were mostly for larger, bulk items that precarious household budgets did not allow for, like furniture, bedding, and clothing.

Purchasing on tick was another strategy for mutual support. Robert Roberts noted in his memoir The Classic Slum that buying on tick could become an emblem of integrity, underlining the complex relationship between shopkeeper and purchaser, and based on trust that money owed would be paid. One Eastender, interviewed in the 1920s, recalled his mother’s reliance on tick, but explained, ‘We wouldn’t call it tick. In Mulberry Street we called it buying on trust.’

Middle-class observers often thought working class consumption was profligate, rather than a strategy for survival. If you have little means of saving safely, to put your money into objects and clothes meant they could be if necessary pawned (or in extremis sold) and thus keep the family and community budget circulating. Buying durable goods was a form of sensible, mutually supportive thrift.

In an article on “Thrift in the Home” philanthropist Henrietta Barnett complained that ‘In most [working-class] rooms there is too much furniture and there are too many ornaments…I have counted as many as seventeen ornaments on one mantelpiece – three, perhaps five are ample. She who aims to be thrifty will fight against yielding to the artificially developed instinct to possess.’

This assessment completely misunderstands saving strategies. Take for example the Sunday suit. From Monday to Saturday it was an idle asset. If cash were needed urgently it made sense to pawn it on a Monday morning; reclaim it in time for wearing to chapel or the pub, depending on your leanings, on Sunday.

What can we learn from all this today? Certainly not to romanticize the tough conditions of life in poverty. The struggle for greater economic, political and social equality must be at the core of any resilient or rapid transition.

But what it can do is challenge our relationship to stuff, and how we use and value it. Idle assets (the equivalent of the modern Sunday suit) can be shared and put to work collectively. Spreading financial risk and sharing it within a community means we develop systems of support and mutualism. Many of these historic examples of saving and credit clubs became critical training grounds for communities learning to organise locally and cooperatively. There is an umbilical cord between the early friendly societies, credit and cooperative clubs and the trade union movement. Such strategies for economic survival were tolerated at a time when it was illegal for working people to meet and discuss their economic predicaments. Such clubs arguably became about all kinds of ways of organising under the radar of the authorities, a way of improving the community ‘lot’.

Remember the phrase – not buying on tick but buying on ‘trust’. Imagine the level of collective understandings that has to exist for such systems to work. Re-building that kind of ‘credit-trust’ reclaims credit from debt, and replaces it with pride and integrity instead.

—

This article is based on Molly Conisbee’s talk for the New Weather Institute at the Hay Festival on 31 May 2016.