As the UK is revealed to be the biggest net importer of carbon dioxide emissions per person in the G7 group of wealthy nations, heterodox economist Katie Kedward spells out five reasons to question the UK government’s progress on tackling the climate emergency

Over the past two weeks, citizens across the UK rallied behind the cause of Extinction Rebellion, participating in non-violent protests and civil disobedience actions to call on the UK government for more ambitious and inclusive action on global heating. Whilst the demonstrations received the support of many MPs, the response from some politicians and corners of the press, including our Prime Minister, has been dismissive at best and derisory at worst. An increasingly common narrative is that the UK has already made laudable progress in reducing its emissions.

However, this analysis is completely at odds with the conclusions reached by the independent Committee on Climate Change (CCC), who warned earlier this year that the UK is woefully behind the urgent progress needed to decarbonise our society. Let’s takes a closer look at exactly why the UK’s self-congratulation on its climate progress is groundless.

- The 2050 net-zero emissions target: lip service but no action

The UK was the first country in the world to implement a legally-binding emissions reduction target earlier this year – a fact often seized upon by the government as evidence of our country’s progress on dealing with the climate emergency. Yet digging a little deeper raises several questions about the government’s true commitment to this target. Firstly, the chosen date to reach net zero emissions, 2050, is markedly unambitious compared to countries like Finland (2035) and Norway (2030). Many fear 2050 is far too late, with climate scientists warning we have just over a decade left to prevent serious catastrophe. Secondly, the UK target controversially allows for the use of international carbon credits to offset UK emissions, despite this having been rejected as a suitable policy by the CCC. Carbon offset programmes, which include the planting of trees in other countries, are criticised for fuelling controversial ‘land grab’ schemes in the global South and for failing to ultimately lower aggregate emissions. Thirdly, the government included a ‘get-out-of-jail-card’, enabling the abandonment of the net-zero target within five years if it deems other countries are failing to take similar action. Given that the UK is currently nowhere near reaching even this relatively unambitious emissions reduction target, the government’s commitment to actually upholding it is more than questionable. It is also a target without a realistic plan to be reached, and in the absence of a clear, ambitious decarbonisation strategy, the existence of the net zero target alone is not acceptable proof of climate progress.

- The creative accounting of UK emissions reductions

Source: University of Leeds

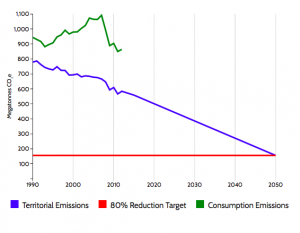

The government also likes to emphasise the recent dramatic fall in UK emissions, citing data that shows a 44% reduction from 1990 levels in 2018. Less often appreciated is just how selective they have been with their choice of emissions data. This headline statistic depicts what are known as territorial emissions: it does not include emissions from international shipping and aviation, and only measures the emissions produced within the UK itself. The effects of trade, specifically all of the products we import, are therefore completely ignored. But with globalisation having moved much UK manufacturing abroad since 1990, this has a distortive effect on UK emissions trends.

Consumption emissions data rectifies this issue by measuring all emissions produced globally to fulfil UK demand. Given that imported goods would not be produced were it not for our demand for them, this approach more accurately depicts the true carbon impact of our high-consumption lifestyles. As research from the University of Leeds demonstrates, UK consumption emissions have actually barely fallen from 1990 levels. The Committee on Climate Change concluded that the UK’s total carbon footprint is actually some 70% larger than that its territorial emissions would suggest, making the UK one of the largest net importers of emissions in the world. In other words, we have effectively offshored our emissions as our economy has grown over the past 30 years. To claim that the UK has dramatically reduced its emissions is therefore both inaccurate and disingenuous. We have a long way to go to reduce the impact of our lifestyles; the use of inappropriate data is an unhelpful obstruction in solving the challenge ahead.

- Not all of our renewable energy is green

The electricity generation sector is one of the areas where the UK has made the most progress in decarbonisation. Yet despite the encouraging closure of nearly all of the UK’s coal power plants, not all of the measures taken to replace this electricity supply have been zero-carbon. Recent analysis by Carbon Brief shows that, whilst renewables overtook fossil fuel electricity generation this year for the first time ever, 30% of renewable energy comes from biomass, specifically the combustion of wood pellets in former coal power plants. With most of these wood pellets imported from North America, the low-carbon credentials of biomass are highly disputed: some researchers estimate that biomass emissions are significantly higher than fossil fuels. Indeed, Drax Power, operator of the largest wood biomass plant in Europe; is the UK’s single largest greenhouse gas emitter. The UK’s electricity generation is on the right trajectory, but biomass cannot be seen as part of the solution. Whilst the UK government continues to support it as a renewable energy source, its commitment to true decarbonisation must be questioned.

- The government has a track record for blocking green innovation….

A series of government policies over recent years have had eye-wateringly negative impacts upon progress in a number of environmental sectors. Solar power has suffered from a loss of subsidies and a massive hike in VAT to 20%, whilst the tax on coal remains at 5%. The government has also blocked onshore wind projects from participating in subsidy auctions, despite it being the cheapest form of renewable electricity generation, effectively banning the construction of nearly 800 ready-to-go projects that had already won planning consent. Progress in improving energy efficiency is also worryingly behind schedule. Heating UK buildings accounts for over a third of total emissions, making it a high priority area to tackle. Yet, the UK government scrapped a pioneering scheme to fund home insulation improvements in 2015, leaving the pace of energy efficiency improvement installations five times slower than they should be. Other target sectors to have no concrete decarbonisation policies in place include transport, agriculture, and waste. With the UK embarrassingly off-track to achieve its legally binding net-zero emissions target by 2050, the current government’s track record for enacting barriers to low-carbon innovation has to be challenged.

- … whilst still financing and protecting the fossil economy

The impact of the UK’s inadequate green strategy is made even worse by ongoing fiscal and policy support to carbon-intensive sectors. The UK has the highest fossil fuel subsidy in the European Union, according to the EU Commission. €12 billion of public funds annually support fossil fuel sectors in the UK, significantly greater than the support given to renewables (Germany, by contrast, subsidises its green sectors by €27 billion!). Last year, the UK also increased its funding to overseas fossil fuel projects to the tune of £2 billion, whilst overseas renewables grants were unbelievably just 0.035% of that figure.

Support for the fossil economy abounds in the policy arena too. In 2016, the government scrapped the 35% tax on UK oil and gas profits, and abolished the Department for Energy and Climate Change, hurriedly squashing its climate responsibilities into the Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). By 2017, audited figures showed that total department spending on decarbonisation within BEIS had more than halved from 2015. Today, the government continues to support fracking as an integral part of the UK’s future energy strategy, despite scientists’ warnings on its environmental dangers and the High Court ruling of this policy position as unlawful. Looking at the government’s recent record, it is hard to dispute that both the UK’s public money and regulatory apparatus are propping up outdated and polluting sectors both at home and abroad, at the expense of urgently needed green innovation. This reality is a serious affront to the notion that the UK is in any way a climate leader.

Taking all of these points together, it is clear that the government is not tackling climate emergency and that a step change in ambition and action is needed. Scrapping fossil fuel subsidies and dismantling the barriers for onshore wind are just some of the obvious decisions our government should have taken years ago. It is clear that securing a sustainable, equitable, and prosperous future for all cannot be achieved by individual behaviour changes alone. But those who have the mandate to implement the wide-sweeping reforms needed are instead hiding behind unambitious targets and dodgy statistics, whilst public funds and regulation continue to support all of the wrong industries. We cannot afford to let our government rest upon its imaginary laurels whilst time slips away. We must use all of the rights and institutions within our democracy, including our democratic right to protest, to hold this government to account and to push for an ambitious green strategy for the future, which is truly realistic in the sense of preventing climate breakdown. The time to act is now.

Katie Kedward is a heterodox economist specialising in the intersection between finance and the environment. She has worked as a Green Finance researcher at ShareAction, the responsible investment NGO, and as a government bond analyst at the Royal Bank of Canada.

Picture: Andrew Simms